Bangladesh today stands at one of the most precarious junctures in its post-independence history.

The departure of Sheikh Hasina, the country’s longest-serving prime minister and a central figure in its political trajectory, has ushered in an interim administration under Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus.

For a nation accustomed to the fierce rivalry between the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), this sudden transition has not only disrupted entrenched political patterns but also left the question of electoral legitimacy dangling over a volatile landscape.

The prospect of holding a free and fair election in this unsettled atmosphere appears increasingly daunting, burdened by decades of mistrust, institutional decay, and the sheer weight of political violence that has scarred the nation’s democratic aspirations.

The void left by Hasina

Sheikh Hasina’s exit has created both relief and uncertainty. For years, her rule was accused of being increasingly authoritarian, with opposition voices stifled, dissent curbed, and elections widely criticised as manipulated.

Yet, Hasina’s presence also provided a strange form of political stability: her dominance left little room for ambiguity about where power rested. With her exit following massive student-led mass protests in 2024, the absence of that overwhelming authority has cracked open a vacuum that no institution or leader seems ready to fill.

Muhammad Yunus, though celebrated internationally as a pioneer of microfinance and as a Nobel Peace Prize recipient, is an outsider in the unforgiving world of Bangladeshi partisan politics.

His ascension to the role of interim prime minister has been met with scepticism from both major political camps.

To the AL, Yunus represents a betrayal—someone who has stepped into a leadership role after Hasina’s departure under international pressure.

To the BNP, Yunus is not a saviour but rather a technocrat with no organic political constituency, a temporary figure whose presence merely delays the party’s ambitions for full restoration of power.

In such a climate, it is unclear whether Yunus possesses the authority, political network, or grassroots legitimacy to ensure a credible electoral process.

Institutions in disarray

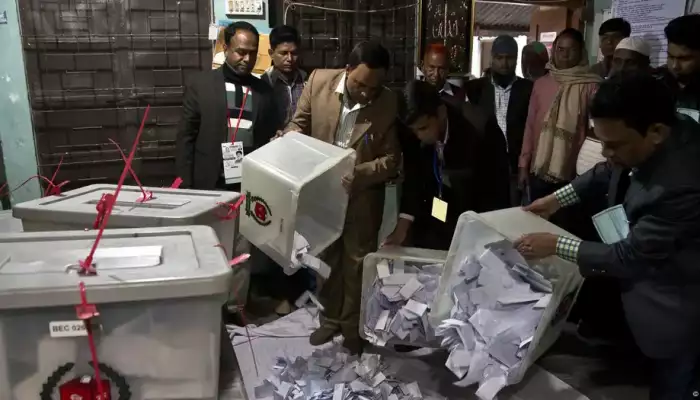

Bangladesh’s institutional weakness compounds the crisis. The Election Commission, already mistrusted after its role in overseeing widely disputed polls, remains deeply compromised.

Civil services and law enforcement agencies, long accused of partisan loyalty to Hasina’s government, now find themselves caught between a fragile neutrality and the temptation to maintain old allegiances.

The judiciary, though nominally independent, has often functioned in tandem with the political executive, raising questions about its ability to act as a safeguard against electoral malpractice.

In such a context, even the promise of a neutral caretaker government—a model that historically provided some measure of trust during transitions—rings hollow.

Yunus’s interim administration lacks the deep political machinery required to wrest control of the electoral apparatus from actors loyal to partisan masters.

That deficiency makes the task of staging a genuinely free election appear less like an opportunity for democratic renewal and more like an invitation for deeper conflict.

The weight of polarisation

Bangladesh’s politics has always been defined by deep-seated polarisation. The AL and BNP have cultivated not just competing ideologies but entire parallel universes of loyalty, patronage, and historical narratives.

This entrenched rivalry ensures that any election is less about policy than about survival—an existential struggle in which losing power often means political persecution, exile, or even imprisonment.

Hasina’s departure has not softened these rivalries. On the contrary, it has intensified them.

BNP supporters, long marginalised and targeted under AL rule, are eager to reclaim space.

Meanwhile, AL loyalists, fearful of retribution, remain unwilling to concede without resistance.

The danger is that under Yunus’s leadership, without the muscle of a strong political organisation, the interim government may find itself unable to contain this simmering competition.

Electoral campaigns, rather than being exercises in democracy, may instead become violent battlegrounds where each side seeks to demonstrate dominance through force rather than ballots.

Street power versus electoral legitimacy

Bangladesh has a long history of street protests and extra-parliamentary agitation.

With an election looming under Yunus’s interim rule, the streets are once again likely to become the main theatre of politics.

Already, reports of clashes between student wings, union groups, and local cadres of both AL and BNP have emerged, signalling the volatility that lies ahead.

The spectre of hartals (general strikes), transport blockades, and mass demonstrations looms large.

In such an environment, the election itself risks being overshadowed by the contest for street power.

If the BNP perceives that Yunus is leaning, however unintentionally, toward retaining AL influence in the electoral framework, it may resort to boycotts or violent agitation, as it has done in the past.

Conversely, if AL fears being dismantled through a fair contest, it may mobilise its vast grassroots machinery to intimidate voters, disrupt polling, and delegitimise the process.

The result could be an election marred not only by irregularities but by widespread bloodshed, with the interim government reduced to a passive observer.

External pressures and expectations

International actors have inevitably inserted themselves into Bangladesh’s electoral moment.

The United States, the European Union (EU), and regional powers like India are all watching closely, each with its own strategic interests. While Washington and Brussels have emphasised democratic credibility, India remains primarily concerned about regional stability and security.

The Yunus government, buoyed initially by international support, is now caught between external expectations and internal resistance.

Pressure from foreign capitals to deliver a free election is strong, but such pressure risks backfiring domestically, where suspicion of foreign meddling runs deep.

The shadow of violence

Perhaps the most alarming feature of the post-Hasina transition is the looming threat of political violence.

Bangladesh’s history is riddled with assassinations, coups, and bloody confrontations between rival factions.

As the interim government struggles to assert control, there is every reason to fear that electoral violence could spiral into something far graver.

Already, marginalised groups, including religious minorities and rural activists, express concern that they may be targeted in the course of political reprisals.

The possibility that violence could derail the entire electoral timetable is real.

If polling stations become flashpoints of intimidation and bloodshed, the interim government will have little recourse but to either postpone elections or push through a process that lacks legitimacy.

Both scenarios would only deepen the crisis, prolonging uncertainty and eroding public faith in democratic mechanisms.

A precarious road ahead

Bangladesh’s future under Muhammad Yunus’s interim leadership is defined by contradictions.

On paper, the moment represents an opportunity to reset the country’s democratic trajectory after years of "authoritarian drift" under Hasina.

In practice, the reality looks far bleaker. The combination of institutional weakness, partisan polarisation, street-level violence, and external meddling makes the task of holding a free and fair election nearly impossible.

The real tragedy is that the Bangladeshi people, who have endured decades of authoritarian excesses and flawed elections, may once again be denied the basic dignity of a credible vote. Instead, they face the likelihood of yet another electoral cycle that entrenches mistrust, fuels violence, and diminishes hope in the democratic project.

In the precarious condition of post-Hasina Bangladesh, Muhammad Yunus presides not over a hopeful transition but over a fragile experiment teetering on the edge of failure.