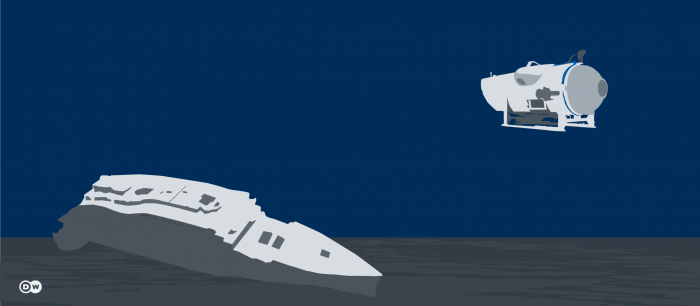

The search continues for the missing tourist vessel with five people on board, at depths of up to 4,000 meters. How do submersibles deal with the pressures of the deep sea — and how deep can they go?

The Titanic was once considered unsinkable. But five days after setting off on its maiden voyage to New York in 1912, what was then the world's largest cruise ship sank. Since then, it has captivated generations of people — including researchers, but also more and more tourists.

"This is your chance to step outside of everyday life and discover something truly extraordinary" — that's the slogan OceanGate Expeditions uses to advertise its tourist expeditions to the Titanic shipwreck.

The price of a ticket for a trip to the deepest parts of the sea: $250,000. Not a price that would be affordable for ordinary tourists, but acceptable for wealthy vacationers.

On board the currently lost tourist vessel Titan are, among others, British billionaire businessman and adventurer Hamish Harding, along with the British-Pakistani management consultant Shahzada Dawood and his 19-year-old son. An intensive, multinational rescue effort is now underway.

How hard is it to recover a submersible?

US and Canadian crews are working "around the clock" to search both on the surface and under the sea. But efforts to locate the boat are extensive and difficult.

According to US Coast Guard reports, an area "the size of Connecticut" has already been flown over to look for signs that the aircraft has surfaced, while military aircraft and commercial vessels have also joined the search.

Difficult conditions prevail at the site where the Titan is missing. The Titanic shipwreck lies at a depth of around 3,800 meters (more than 12,400 feet) in almost complete darkness. The water pressure is high and the temperature close to freezing.

"Techniques vary, but in this depth of water, a sonar search system would have to specialize in a very narrow beam but a high enough frequency to resolve a small submersible. The search for Emiliano Sala's plane a few years ago, an object of similar size, took less than three days, but in shallower water," Jamie Pringle, a forensic geoscientist at Keele University, England, told reporters.

In Titan's case, there are only two possibilities. "If, contrary to expectations, the boat drifts to the surface and cannot be located due to the low freeboard [distance from the water to the upper deck — Editor's note], the chances of being found are realistic," the German Navy estimated. "However, this is countered by the fact that a distress signal would have been sent in such a case."

If the submersible has sunk to the seabed, this would make finding and rescuing the vessel particularly difficult. The seafloor is much more rugged than on land, with many stratifications and continental shelves, as well as ocean currents.

Light does not travel easily through water, blocking most communications. "Unfortunately, the seawater below the surface blocks the propagation [of electromagnetic waves] very quickly: no radar, no GPS, and spotlight or laser beams are absorbed within a few meters," said Eric Fusil, director of the Shipbuilding Hub for Integrated Engineering at the University of Adelaide, Australia.

Because of the submersible's design, it's not possible to deliver fresh oxygen from the outside, according to the German Navy.

How long can Titan sustain deep-sea pressure?

The water pressure 3,800 meters down at the site of the Titanic wreck is roughly 400 atmospheres (6000 PSI) — about the same as having 35 elephants on your shoulders.

This makes deep-see exploration a major technological feat, requiring submersibles and submarines capable of withstanding huge amounts of pressure over long periods of time.

"Any deep divers know how unforgiving the abyssal plain is: going undersea is as, if not more, challenging than going into space from an engineering perspective," said Fusil.

The Titan is made of carbon fiber and titanium, materials that can withstand the pressure at depths of up to 4,000 meters. The craft's hull is designed to protect the crew from the water pressure.

However, deep-sea Navy rescue submarines struggle with depth and have a maximum range of 2,250 to 3,000 meters. If the Titan has sunk to the seabed and is unable to surface under its own power, Navy submarines would have a hard time rescuing it.

"Even military nuclear-powered submarines are limited to depths between 0-500 meters and could only use their sonars [active or passive] to detect any sign of the Titan, without a possibility to get closer," Fusil told reporters.

Exploring the depths

This is not the first deep-sea expedition in which tourists have explored the deepest recesses of the ocean.

In 2012, Canadian filmmaker James Cameron set off on a deep-sea expedition to the deepest point on Earth in the Mariana Trench aboard the submersible Deepsea Challenger. He collected data and footage at depths of around 10,900 meters. His deep-sea voyage came exactly 100 years after the Titanic sank to the ocean floor. Cameron has has also visited the Titanic wreck in earlier deep-sea voyages.

In 2019, American explorer and private investor Victor Vescovo set a world record in the Mariana Trench, where he reached 10,928 meters — 16 meters deeper than the previous record set by Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard in 1960.

Together with missing billionaire Hamish Harding, Vescovo also set a world record for the longest time spent in the deepest part of the ocean on a single dive when they spent four hours and 15 minutes traversing the Mariana Trench in 2021.

On board, the Titan is also the former French Navy Captain Paul-Henri Nargeolet, who has often dived to the Titanic wreck. A few years ago, in an interview with the Irish Examiner newspaper, he said, "In deep water, you're dead before you can realize what's happening."

The 77-year-old has been head of the research program at RMS Titanic/Phoenix International, which owns the salvage rights to the wreck, since 2007.

Rescue workers are still searching for the five people aboard the Titan, but it's a race against time. "Let's hope for the Titan and its passengers that they can return safely to the surface," said engineering expert Fusil.