It may be useful to imagine for the duration of Europe's upcoming election season that we live in a world without public polling. Would that make further populist surprises look more or less likely?

The post-Brexit, post-Trump world is not necessarily "post-truth" despite a certain blurring of lines between fact and spin. It is, however, definitely post-poll. US pollsters will now conduct post-mortems of why they failed to predict Donald Trump's victory. When the soul-searching and data-mining is done, they'll admit some technical flaws, and then explain that their polls weren't really all that wrong, just misinterpreted and misused. None of this will matter to the general public: They want accurate standings in what they've come to see as a sport. If pollsters cannot provide those, their work is irrelevant. The post-Trump world is also post-expert.

It's not easy to dismiss polls as predictive, however. A week before the election, I sat at the sports book at the Wynn casino in Las Vegas and listened to a lawyer named Robert Barnes rattle off reason after reason why he was betting big money on Trump with UK bookmakers. And yet I wasn't entirely convinced, because I'd been reading about the polls everywhere. I wrestled with the need to conceptualise the election as anything other than a baseball game seen through a statistician's eyes -- the way probably sees it.

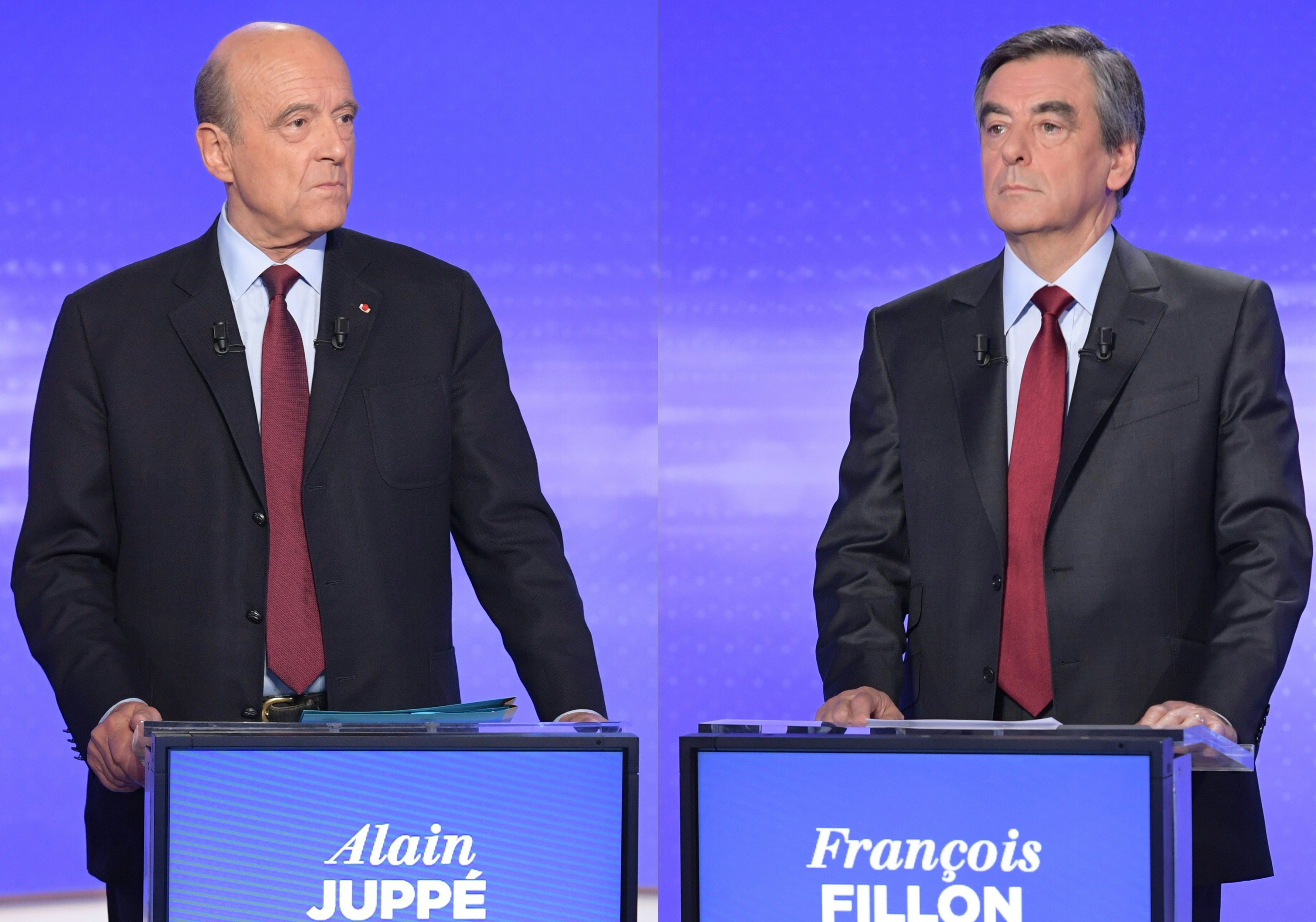

I'm going to try not to make this mistake for the 2017 elections in the Netherlands, France, Germany and possibly Italy. French pollsters, whose data predicts National Front leader Marine Le Pen will reach the run-off round of the vote then lose to a center-right candidate make disclaimers that sound alarmingly like their US colleagues at the primary stage of the presidential race, and it's a good reason to steer clear.

The first thing I should have looked at in the US election was the social network engagement and search metrics. They were confidently in Trump's favour, reflecting the enthusiasm of his supporters and the lack thereof in the Clinton camp. It's an alarming sign that nationalist populist Geert Wilders leads Prime Minister Mark Rutte in Dutch Google searches, Le Pen is a more frequent search term in France and the anti-immigrant AfD party is ahead of Chancellor Angela Merkel's CDU in German ones. Sure, there may be some smart, complacent explanations for that -- the incumbents are better-known than the challengers, so it may just be curiosity -- but post-Trump, I'm inclined to think this kind of curiosity is a sign that people are actively looking for alternatives to the status quo. As Taha Yasseri and Jonathan Bright of Oxford University wrote in a paper on predicting the outcomes of European Parliament elections using the traffic to Wikipedia pages, "voters are cognitive misers who are more likely to seek information on new political parties and when they are actually changing a vote."

Even though European countries, especially Germany and France, are not as internet-dependent as the US, it will be instructive to see social network engagement data -- likes, shares, retweets -- when the election season gets going. If the data match the search trends, incumbents will be in trouble.

It's also useful to pay more attention to econometric models. In the US, they are tracked by PollyVote.com, a project led by Andreas Graefe -- a German affiliated with both Columbia University and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. The German university funded a similar effort for its country before the parliamentary election of 2013.

Helmuth Norpoth, the SUNY Stony Brook professor, built two models that predicted Trump's victory (one based on primary results and the other on the idea that election results run in cycles). He was so sure he was right that he bet on Trump. Norpoth, who is German, built a model for German elections, too -- the Kanzlermodell. It takes into account the parties' "voter retention" from previous elections, the "wear and tear" on the incumbent measured in the amount of time served, and the popularity of the current chancellor one to two months before the election. The model predicted Merkel's victory in 2013. Another model, by Mark Kayser and Arnd Leininger of the Hertie School of Governance, expanded on Norpoth's work, adding the German economy's performance relative to European peers. The Benchmark Model, as they called it, also worked well in 2013, and I'd be inclined to trust its output in 2017, too.

Like US elections, German ones are rather accurately predicted based on the ruling coalition's economic performance. The Merkel government has done well on that front, and that tells me she may be in a better position going into the election than the US Democrats were.

That method -- with unemployment a major variable to watch -- has also worked well in France, predicting vote results including Francois Hollande's defeat of Nicolas Sarkozy in 2012. Hollande's economic performance has been abysmal, and a loss for the Socialists in 2017 is all but inevitable -- but it's hard to enter a maverick like Le Pen into such a model because it works best for two-party systems such as America's, or the French one before the populist boom. The same problem applies to the Netherlands and Italy, where the populist parties appear to be breaking traditional molds.

Anyone seeking a framework for looking at all the 2017 European elections that excludes the polls or uses them as one of many inputs would probably do well to look at search and social network engagement in combination with local models that use data on previous voting patterns and some economic indicators. Not enough such data is available at this point, but merely thinking about the factors that go into such models produces far more uncertainty about the outcomes than polls generate.

But there is a less scientific approach that might be even more reliable. If you're traveling in any of the European countries facing elections, talk to the people you meet. If I have understood anything after traveling extensively in the US during the election campaign, these casual conversations should be seen as a major input, whatever sociologists say about the value of such anecdotal data. Eventually, if polls remain as useless as they've been in many recent high-profile votes, politicians too may learn to talk to voters the way they did in the era before polling. - Bloomberg View