Can messy, polarised democracies ever get anything done? Could real reformist laws ever be passed by legislatures obsessed with partisan point-scoring? Across the liberal-democratic world, it seems that obstructing legislation by any means necessary is now part of politics as usual. Partisan gamesmanship, increasingly, looks like a genuine threat to the legitimacy of legislatures -- and of democracy itself.

And yet, in New Delhi this week, democracy worked as planned.

The upper house of India's parliament is not usually a quiet place. Independent India's founding generation expected the level of debate there to be elevated, with elder statesmen from all parties and states rising above the politics of the moment.

That's not how things worked out. Because the government of the day rarely has a majority in the upper house, that's where the opposition makes its presence felt. And so it's frequently disrupted by slogan-shouting, walkouts and adjournments -- at one point in the last government's tenure, it had worked normally for about 2 per cent of its allotted time, for just over an hour.

If you tuned into the debate on India's proposed goods and services tax this week, you might well have thought you'd fallen through a crack in space-time into a dimension where parliament worked exactly as India's founders imagined. When the Council of States debated amending the Constitution to make space for the GST, it took almost eight hours and more than 30 speeches. It was conducted in the most decorous manner possible.

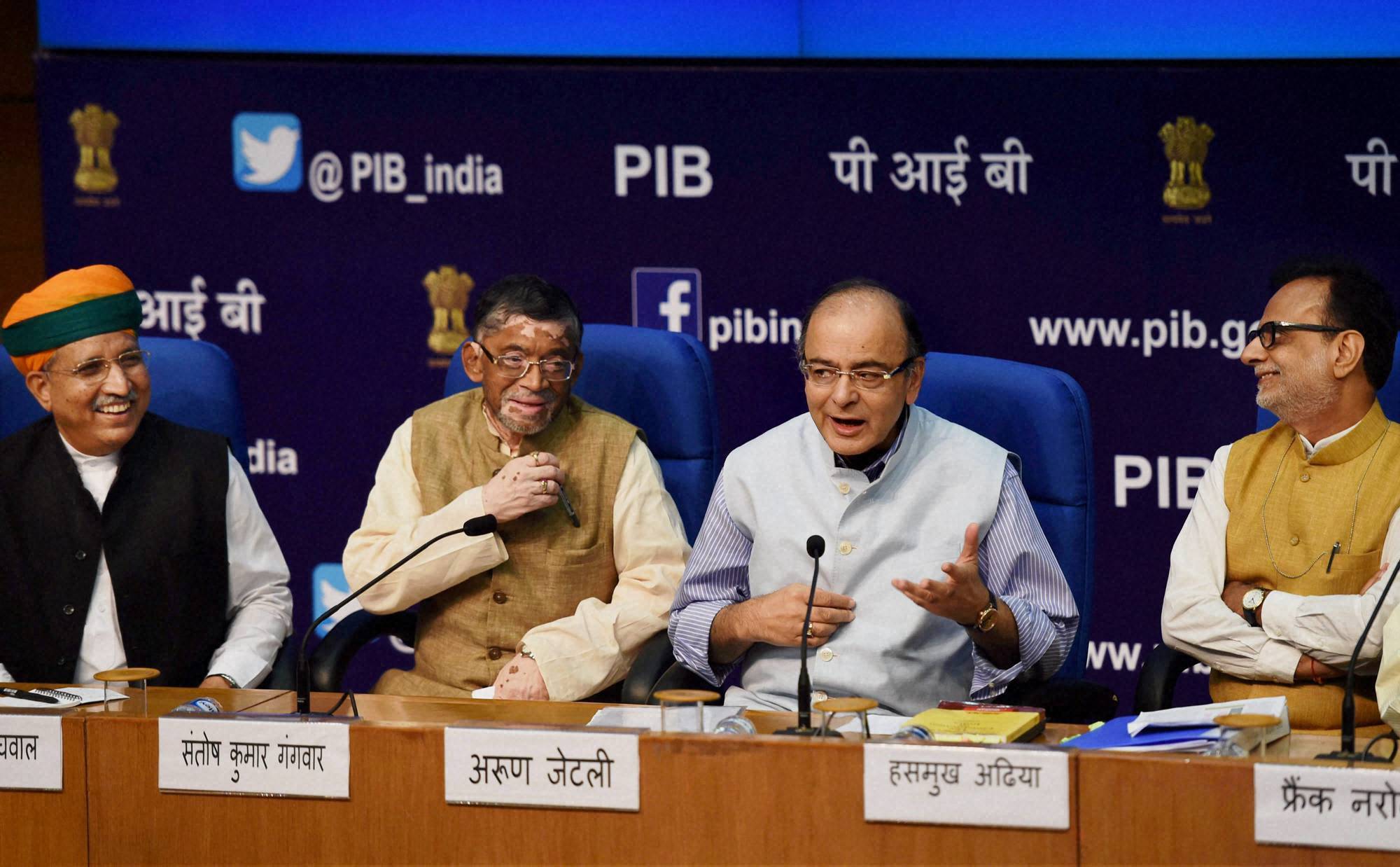

The amendment eventually passed, and should be cleared by the lower house soon. Once the constitution is amended, and supporting legislation passed, the plethora of central- and state-level indirect taxes that companies currently face will hopefully be replaced with a simple, national tax. In India, it's frequently easier to trade with the outside world than with another state; the GST would be the biggest step the country has ever taken toward becoming a single market.

As India contemplates its most momentous legal change since the first rush of economic liberalisation 25 years ago, the celebrations are somewhat muted by the fact that it took 12 years to get here. What hope for any country with such divided politics? Where lawmaking is so sclerotic? The head-shaking about partisanship mirrors concerns from Canada to Ghana.

Yet, as the GST debate showed, the deep divisions that have become a characteristic of 21st-century legislatures don't need to hold back truly transformative laws. Yes, where you stand on some laws depends on where you sit; the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi will now seek to take credit for a reform that Modi himself blocked for years when his party was in the opposition.

But what some of the head-shakers missed is this: Not all the opposition was pointless posturing. The years-long debate on a unified tax system led to many crucial improvements in the legislation. The number of politically sensitive sectors exempted from the new tax had to be reduced to a minimum -- revenue from alcohol and real estate in particular often underwrites political populism and corruption in India. The governments of India's states, concerned about lost revenue, had to be given assurances of one kind or another. Eventually, the central government promised to make up any shortfall in the states' tax collections for five years.

After that was sorted out, another problem turned up. To sell the GST to states with big manufacturing clusters -- which were in danger of losing taxes to states that tended to buy rather than produce goods -- the government made changes to the tax structure. It introduced an additional 1 percent tax on all goods that moved over state borders. Naturally, this caused an uproar -- the point of the GST is to make India a single market, and to ensure trucks don't stand idling at the many municipal and state boundaries that crisscross the country. The bill, with the 1 percent levy, passed the lower house where the government has a majority. But when it reached the upper house, the opposition noisily blocked it.

In other words, behind the polarsation and obstruction were very real differences on what policy would work, and what compromises were needed.

Eventually, after months of negotiations, the government gave in, and the 1 per cent levy was scrapped. Simultaneously, the opposition dropped its demand for a constitutional ceiling on the tax rate. The eventual legislation was much, much better than the original -- not in spite of, but because of the confrontation and disputation. All those who dismissed India's delay in passing a clearly vital law as signs that the system couldn't work could not have been more wrong.

"GST" stood for "good sense triumphs," said the ex-finance minister who began the process in 2004. Perhaps that's a little too exuberant; a lot of work still needs to be done. But certainly there are lessons for many other countries -- and for those worrying that entrenched positions and confrontation are destroying deliberative democracy worldwide. It turns out that, even after years of trench warfare, big breakthroughs are still possible. - Bloomberg View