Scientists are finding more and more causal links between climate change and frequent extreme weather events that affect food production.

So, the European Union is looking at whether it should relax its legislation on genetic engineering and GMO crops.

The thinking is that relaxed GMO laws could push the development of more resistant crops in an effort to guarantee food security.

Experts say it could also help Europe stay up-to-date with scientific developments in genome editing techniques.

European Union governments have been pushing for less strict regulations on genetically modified plants, including those produced with "new genomic techniques" or (NGT).

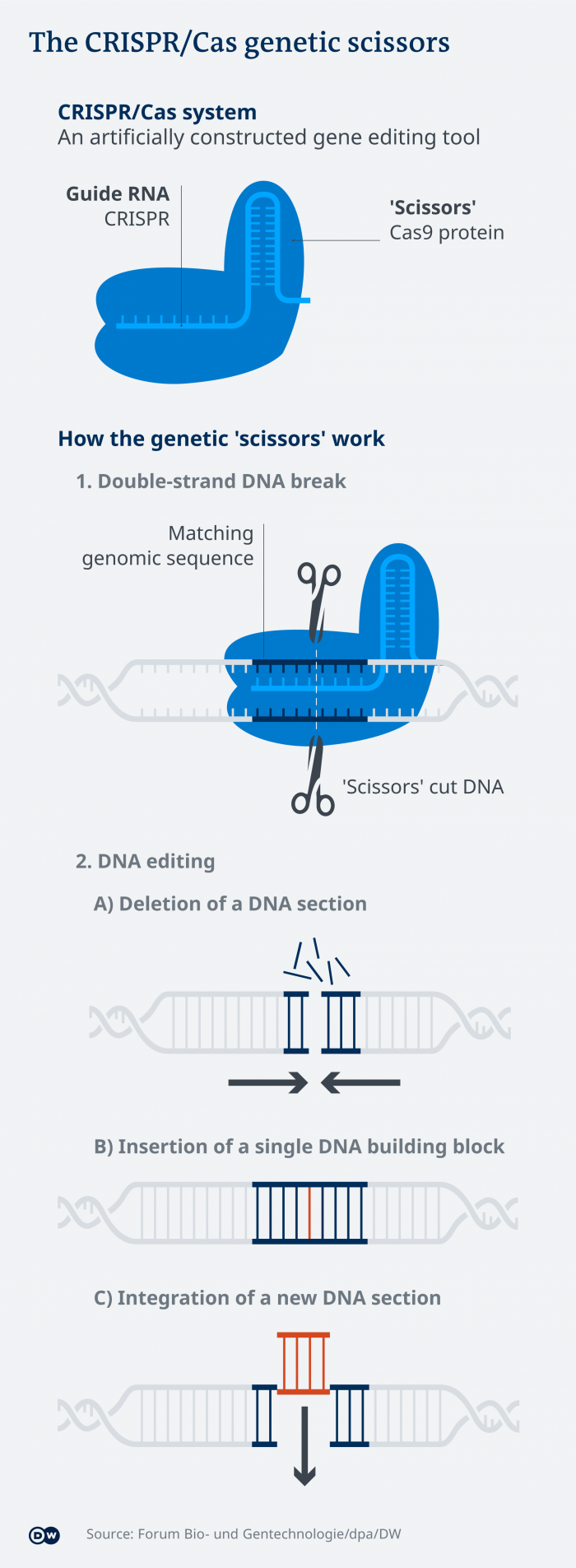

Any gene editing technology developed after 2001, such as CRISPR-Cas9, is considered a new genomic technique. CRISPR-Cas9 is like a molecular scalpel that can make precise modifications in a DNA sequence.

"Plants produced by new genomic techniques can support sustainability," said Stella Kyriakides, the EU's Health Commissioner, in April 2023.

What's in the EU's draft legislation on GMO crops

A draft of the proposed legislation was leaked in June 2023 and published by the Agricultural and Rural Convention, ARC2020, a political organization in Europe.

According to the leaked document, the proposal removes some NGT plant varieties from existing regulations on GMOs, based on two main criteria.

First, the NGT should not contain any genetic material from other organisms.

And second, they should not differ from conventionally bred plant varieties.

These plants would be classified as NGT-1.

The draft also allows for NGT plants that do not fall into this new NGT-1 category when they meet sustainability criteria set out in the European Green Deal. These include resistance to droughts or heat, pathogens, higher yield, or "improved" nutrient content.

However, the legislation excludes from any exemptions herbicide-resistant NGT plants, such as glyphosate-resistant plants, which would continue to be handled by existing GMO laws.

Experts comment on EU's proposed GMO law

Ahead of the publication of the draft legislation, the German Science Media Center (SMC) asked several experts for their opinions, and we have quoted some of them for this article.

The comments appear to suggest a mostly positive consensus among those scientists who were asked by the SMC, but some raised doubts about the science behind the draft legislation.

Experts who have read the draft say the new legislation aims to differentiate clearly between genetically modified plants that have been grown using "new techniques" and those plants grown with classic plant-breeding techniques.

Classic plant breeding is when humans selectively choose plants with desired characteristics and reproduce them. Those traits or characteristics are pre-determined by a plant's genes. So, if you select a big banana-bearing plant, you are indirectly selecting the genes responsible for that.

"These are small genetic changes that could in principle also be caused by natural mutations," said Matin Qaim, Professor of Agricultural Economics and Director at the Centre for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn. "These plants are just as safe as conventionally grown ones."

What genetic changes are allowed?

The leaked documents suggest that the new law would allow NGT plants that do not carry genetic material from other organisms, such as a bacterial gene that contributes to making plants glyphosate-resistant.

NGT plants are not allowed to differ from conventionally-bred plants by more than 20 genetic alterations in what scientists refer to as "predictable DNA sequences".

Some experts comment that it's difficult to tell at this stage whether the new criteria will work in practice.

Andreas Weber, Head of the Institute for Plant Biochemistry at Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, said they will only know once they have worked with the new regulations whether it will limit their ability to do research on new crops.

"Compared to conventional breeding methods, [...] 20 modifications are very few... the regulations [may] have to be readjusted and adjusted upwards again in a few years," said Weber.

Two limits on genetic modification

It's important to understand that we're talking about two different kinds of limits.

The proposal includes one limit on the number of genetic modifications in a crop.

In order to perform a genetic modification, scientists alter nucleotides, which are the building blocks of DNA.

And the proposal sets a second limit on the number of nucleotides that can be replaced or inserted to complete the genetic modification.

Most of the scientists asked by SMC accepted the limit as okay, but it did not go without criticism.

"There is no robust scientific evidence or justification for an arbitrary limit of 20 nucleotides," said Angelika Hilbeck, a researcher at the Institute for Integrative Biology, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ), in Switzerland.

The 20-nucleotide limit also doesn't apply to DNA sequences that already exist in the plant's "gene pool". A gene pool is the combination of all the genes that exist in the whole population of a species.

"Sequences within the gene pool of a species can also be recombined through classical breeding — after all, that is the principle of breeding," said Weber.

Sustainability and applications

Overall, the scientists in SMC's survey agreed on keeping herbicide-resistant plants out of the looser regulation.

"Combining seeds and herbicides could create dependencies that could be detrimental to agriculture," added Weber.

"Wheat and potatoes, for example, are well-developed with built-in fungal resistance, which means that treatment with fungicides can be drastically reduced," Qaim.

New drought and heat-tolerant varieties are also in development.