London: London's High Court has granted permission to asylum seekers in the UK and charities supporting them to appeal against a ruling that deemed the UK government's plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda lawful.

Previously, in December 2022, the High Court ruled the government's Rwanda asylum plan breached neither domestic laws nor the United Nations Refugee Convention.

The court ruling was met with disappointment, and Asylum Aid — a charity organization that offers legal advice and support to people seeking refuge in the UK — applied for permission to appeal the December judgment, arguing the High Court had "erred" in its ruling.

The organisation claims the Rwanda asylum procedure is unfair because it gives asylum seekers — generally new arrivals to the UK who are in detention — just seven days to grapple with the fact that they are being considered for deportation to Rwanda.

According to Asylum Aid, this short time frame would not give asylum seekers enough time to find legal representation to argue their case.

After a hearing at the High Court on Monday, Judges Clive Lewis and Jonathan Swift granted permission to legally challenge Britain's Rwanda asylum policy at the Court of Appeal.

This decision means that no deportation flights will be taking off from the UK to Rwanda any time soon, and asylum seekers can challenge the entire deportation plan at the Court of Appeal.

Sophie Lucas, a lawyer at Duncan Lewis Solicitors who represents some asylum seekers and refugee charities like Care4Calais, welcomed the court's decision.

"The six asylum seekers who we represent who were due to be sent to Rwanda can continue to now challenge aspects of the lawfulness of the whole plan at the Court of Appeal, which I imagine would take place closer to Easter. Whichever party succeeds in the Court of Appeal, it is likely that this will go to the Supreme Court," she told DW.

"But this entire legal process is a torturous ordeal for the asylum seekers, who will continue living in limbo until the complex legal procedures are over. They will have to wait months on end to find out if they can actually start rebuilding their lives in the UK," she added.

Meanwhile, the British government is prepared for the lengthy legal process and remains committed to its asylum policy.

"Unfortunately you have got to let that play out," UK Home Secretary Suvella Braverman said at an event during the British Conservative Party's October 2022 conference, adding that the legal battles in the case could go all the way to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

The UK's Rwanda asylum plan

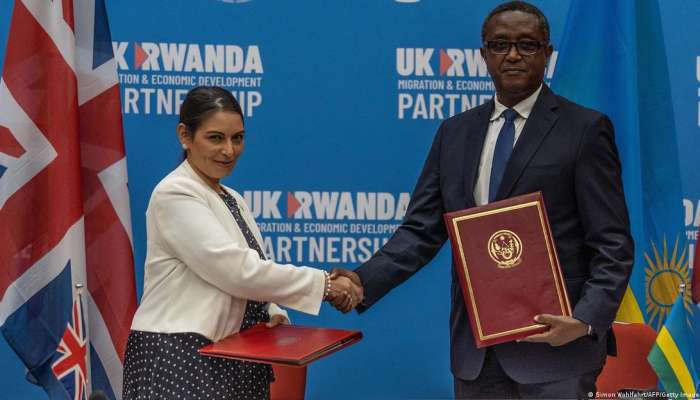

Last April, Britain's then home secretary, Priti Patel, signed an agreement with Rwanda in which the latter would receive asylum seekers who had arrived in the UK illegally.

The policy was introduced in a bid to stop people seeking refuge from trying to enter the UK by small boat or truck across the English Channel.

While the first deportation flight was set to take off to Rwanda on June 14 last year, several protests and legal challenges raised by rights groups and immigration lawyers, as well as a last minute intervention by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), grounded the flight and asylum seekers found their deportation flight tickets cancelled.

Prior to the High Court's final ruling on the policy, the United Nations' Refugee Agency (UNHCR) also expressed concern about the Rwanda arrangement in a statement, saying "it breaches international law and shifts the UK's responsibilities onto a country already striving to manage existing responsibilities to a large refugee population from neighbouring countries."

But on December 19, 2022, the High Court ruled the government's asylum plan was lawfu,l and the UK also said it would pay Rwanda £120 million (€135 million/$146 million) over the next five years to support the scheme.

'Rwanda is not safe'

Still, government figures show that despite the strict asylum plan to deter migrants from entering the UK, a total of 45,756 crossed the English Channel in 2022 — 17,000 more than made the crossing in 2021. And many more seeking refuge will continue to make the dangerous journey.

Jumaize Abdulrahim, who fled violence in South Sudan, told DW that he was keen to live in the UK because it has always been his dream.

"My asylum papers haven't been accepted in Calais, France, and it is very hard and expensive for me to get a visa to the UK. I have fled some dangerous situations and am eager for safety, which I know the UK will provide," he told DW in November last year.

"I also speak the language, so it would be easier for me to find a job in the UK," he said, adding that this was a shared sentiment for many people like him, living in limbo in the camps of Calais.

Abdulrahim told DW he was aware of the British government's controversial Rwanda asylum policy, but hoped for change.

"Rwanda is not safe. There are refugees suffering there even now. It is not humane to send us there. It also can't work by law. Even in the eyes of God it is not lawful, because this is about human beings," he added.

Last week, referring to an increase in the number of people fleeing violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwandan President Paul Kagame said his country "cannot keep being host to refugees for which later on, we are accountable in some way, or even abused about."

According to a report by the nongovernmental organisation (NGO) Human Rights Watch (HRW), the president's statement represents the politicisation of refugees.

"Kagame's latest attacks on human rights, this time refugee rights, just adds to the mounting evidence that Rwanda is not a reliable, good-faith international partner, and that the UK's plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda is based on falsehoods and cynical politics," Lewis Mudge, Human Rights Watch's Central Africa director, said in a statement.

Roberto Forin, European regional coordinator at the Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) global data and analysis network, told DW that most people crossing the English Channel are vulnerable individuals in need of international protection. "It is demonstrated by the fact that the majority of them claim and obtain asylum once in the UK," he said.

"The plan has so far failed to play a deterrent role, it undermines the established international refugee protection system and proposes to send people to a country with a questionable record on protecting human rights. Instead of de facto evading its obligations under the refugee convention in this manner, the UK should work together with the European Union to uphold international law and cooperate in responsibility sharing and refugee resettlement schemes," he added.